By Mᴀʀʏ Mᴡᴇɴᴅᴇ

Kenya’s flower industry is working through the EU’s stringent phytosanitary requirements, aiming for full compliance to maintain its competitive edge. A recent stakeholder meeting provided essential insights into key challenges, particularly the role of phytosanitary units and traceability, while highlighting broader regional issues impacting the East African flower export market.

What Is a Phytosanitary Unit?

A phytosanitary unit is essentially a defined production area within a farm used to isolate and manage plant health risks. This could be an individual greenhouse, a section of a larger greenhouse separated by physical barriers, or an open field block, depending on the farm’s layout and operational scale.

The primary role of a phytosanitary unit is to support traceability. Growers must be able to identify exactly where their produce originated within the farm. In the event of a pest issue or non-compliance, they should swiftly trace and isolate the affected area without jeopardizing the rest of their production.

For instance, farms with multiple small greenhouses can treat each greenhouse as a phytosanitary unit, coding them accordingly. Larger farms might subdivide expansive greenhouses into smaller, manageable units, provided these divisions meet Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service (KEPHIS) approval. The goal is to ensure clear traceability and minimize the risk of entire consignments being rejected due to isolated interceptions.

Why It Matters

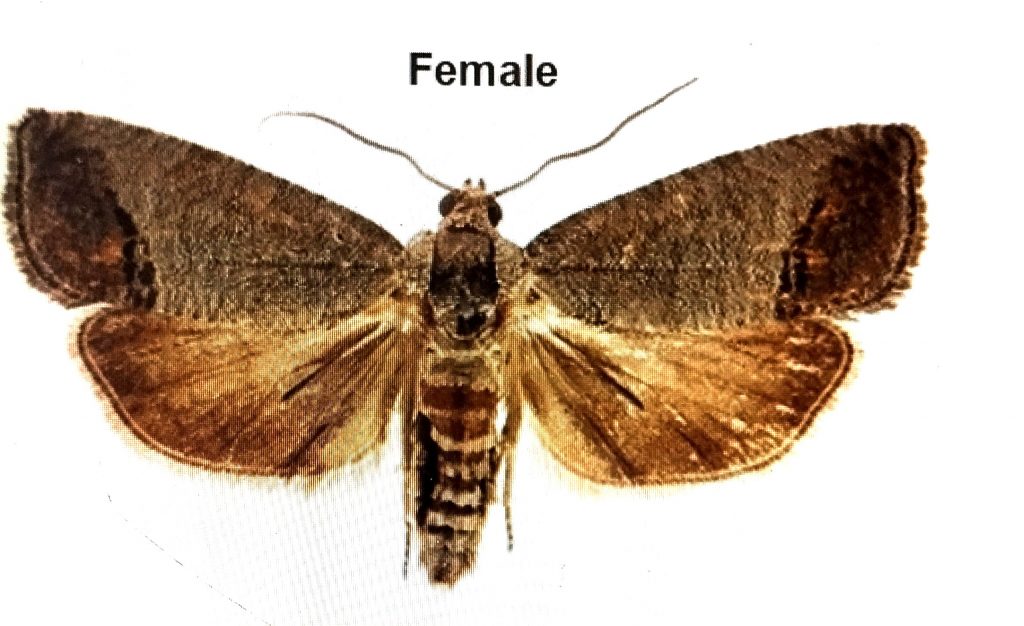

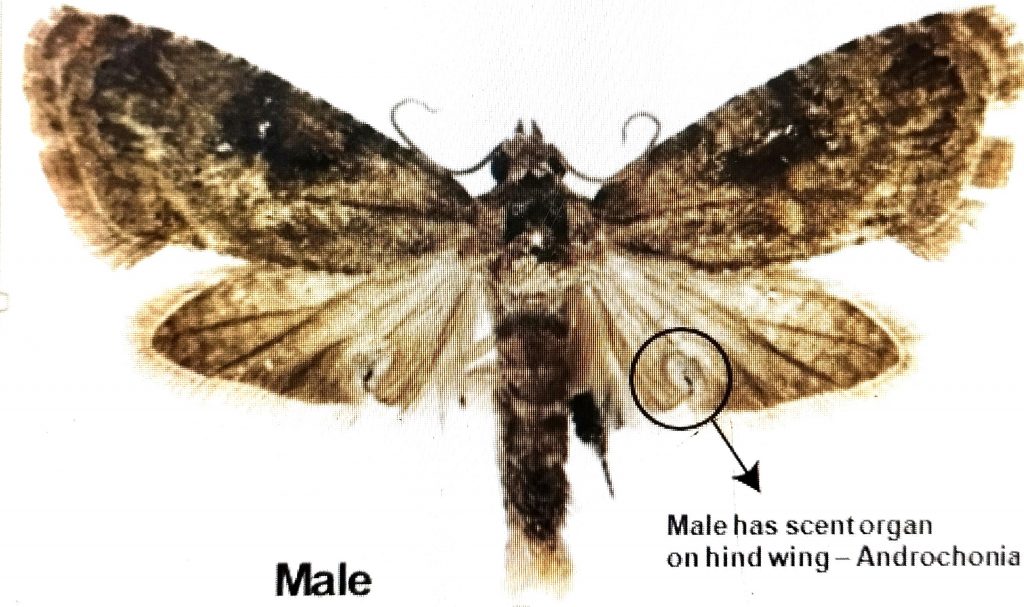

The EU has intensified its scrutiny of flower imports, particularly for pests like False Codling Moth (FCM). Interceptions not only damage Kenya’s market reputation but also indicate system weaknesses. The industry emphasis is now firmly on prevention rather than reaction.

As KEPHIS officials explained, farms are being encouraged to adopt self-regulation strategies. If a problem is identified in one unit, farm managers should suspend harvesting from that area immediately and resolve the issue before resuming exports. This proactive approach is essential to safeguarding the country’s reputation and market share.

Regional Status and Kenya’s Position

Neighboring countries like Ethiopia and Uganda face similar challenges. Ethiopia, benefiting from fewer farms and localized FCM outbreaks, has implemented phytosanitary units with relative ease. Uganda, though smaller, continues to battle persistent FCM problems, with EU inspection levels at 100% for their rose exports. The EU’s stringent stance underscores the importance of effective phytosanitary systems across the region.

Kenya, accounting for approximately 35% of roses supplied to the EU, shoulders greater responsibility. The country submitted its systems approach for EU approval, though the process took longer due to the need for supporting data and inconsistencies in farm-level readiness. Consequently, only farms meeting the compliance standards have been issued traceability codes so far, with others expected to follow once they resolve outstanding issues.

Key Takeaways for Growers

- Traceability codes are mandatory for all EU-bound consignments and must be visible on packaging, invoices, and packing lists.

- Farms must self-regulate and isolate phytosanitary units to swiftly address issues without halting entire farm operations.

- Consolidators must also comply, ensuring that flowers sourced from multiple farms meet EU requirements and are properly coded.

- Pesticide use must align with both Kenyan and EU market regulations. Ongoing harmonization efforts aim to streamline this process and avoid non-compliance.

The industry is actively refining its systems approach, with discussions ongoing about streamlining documentation and improving digital traceability solutions. Meanwhile, stakeholders are urged to stay vigilant, maintain transparency, and foster collaboration to ensure Kenya’s flower exports remain competitive in international markets. One stakeholder noted, “The real effort should be how we can fix our system, not how we can continue exporting while getting interceptions.”