Downy mildew is a fungal disease that causes destruction of leaves, stems, and flowers of the infected plant. Downy mildew causal organism is called Peronosporasparsa and as the scientific name indicates, the production of spores is sparse and therefore this disease is difficult to diagnose and control.

Peronospora sparsa, is a fungus-like eukaryotic microorganism (oomycete), more closely related to algae than to fungi. P. sparsa is an obligate parasite that establishes long term feeding relationship with rose plant and its growth depends on the living plant tissues.

Downy mildew (Oomycete fungi) are referred to as a high risk pathogens because of the following factors;

- Oomycetes fungi are able to spread in an explosive manner under favorable conditions.

- Short development cycle (8-10 days under optimum conditions)

- High potential for reproduction (high quantities of spores)

- Wide propagation by water and wind

- Damage is not reversible: The damaged tissues die in general leading quickly to substantial losses at harvest

- High genetic variability: Rapid appearance of strains less sensitive to specifically acting fungicides possible.

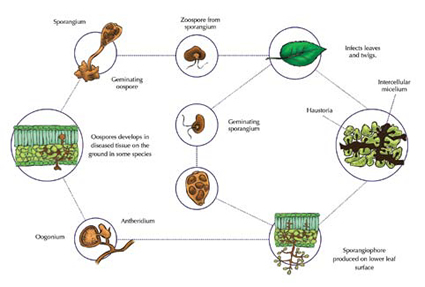

The pathogen grows between the host cells and invades the plant tissues by producing nutrient-absorbing structures called haustoria. Spore production and infection occur during extended periods of cool and humid weather: The sporangiophores and sporangia appear on the lower leaf surface. A complete life cycle can occur in 72 hours. The pseudo fungus penetrates the host through the cuticle and epidermis, and feeds on parenchymal cells via haustoria and intercellular mycelium profuse network.

As the infection progresses, sucrose and other nutrients move from the leaves to new infection zones originated by localized injuries. When sporangia are mature, they spread by the wind to developing foliage and flowers. Symptoms usually develop within 10 days after infection, with sporulation occurring 5 – 10 days later.

P. sparsa has been detected in the cortex of stems and root tissues of symptomatic plants and crown tissues of a symptomatic mother plants used as a source of propagation material the disease therefore starts on bare-rooted, apparently healthy stocks and infect new stems and emerging leaves as they develop.

Downy mildew pathogen thrives best under conditions with 90 – 100% humidity and relatively low temperatures (10 – 24°C). Therefore, rose downy mildew occurs mainly in greenhouses, rather than outdoors. High-risk seasons with a downy mildew incidence >10% coincided with months when the number of hours per day with temperature of 15 – 20°C averaged >9.8 over the month and the number of days with rainfall in the month was >38.7%. The disease starts as small angular yellow spots or chlorotic lesions on the upper surface of leaves These lesions quickly turn into red, purple or dark brown blotches, which are surrounded by a chlorotic halo.

On the underside of the leaves, the signs of the pathogen include occurrence of a light brown mycelium with abundant production of sporangiophores and sporangia, creating hairy appearance. On the stems and Calyx, the disease manifests as dark purple spots that vary in size and may even coalesce inducing death of branches and mummification of flower buds. Foliar symptoms of the disease are usually mistaken for abiotic stresses such as burns or pesticide phytotoxicity, rendering correct diagnosis difficult.

Greenhouse management: Maintaining low humidity levels and avoiding sudden temperature drops during the night is the most effective way to prevent downy mildew epidemic.

What factors favour these conditions?

- Type of greenhouse

- Crop type and density

- Drip irrigation

- Nutrition status

- Human activity; prunning, scouting, spraying, harvesting etc

Disease Management

Cultural Control

- Destroy rose debris from previous crops — spores can overwinter in leaves and canes, then the downy mildew can attack new plants.

- Try to water early in the day or whenever leaves will dry quickly, to ensure dry foliage at night

- Even though fans might move spores, you should use them along with venting to reduce humidity and leaf wetness

- Hungry plants are more susceptible to downy mildew. Maintain a balanced fertility program to protect your crops

- Space plants to allow rapid drying of leaves. If the leaves are very touching, the canopy closes in and the humidity increases.

- Use resistant varieties for low maintenance plantings

Chemical Control

Chemical control of downy mildew in roses should be based on the recommendations of the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC).

Choosing the most effective fungicides to prevent or eradicate rose downy mildew can be tough. Downy mildew requires a well-managed chemical spray program starting early with a rotation of chemicals for prevention. Rotation of fungicides from different chemical groups to avoid development of resistance by the pathogen. Fungicides for use against downy mildew can be categorized as either preventive, early or late curative products.

The disease also overwinters in the crop that was infected in the previous season. The fungus may overwinter in stems as dormant mycelia without oospores. This is the primary inoculum of the disease and upon reaching the favorable conditions, the disease infects new stems.

The preventive fungicides (mancozeb, propineb, copper compounds etc) must be applied before an infection period begins. New growth following application will not be protected.

Early curative products work against spore germination, sporangia elongation and penetration while “Late curative products” deal with intracellular infection level (by this time symptoms are visible to the eye).

Crop nutrition: Nutritional elements such as nitrogen (N), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), boron (B), Silicon (Si) and nutrients ratios such as N: K ratio are important in increasing resistance to obligate parasites like P. sparsa.

Biological control: Use of Bacillus subtilis as a rotation in a management program of P. sparsa.

Dr. Samuel Nyalala, Department of Crops, Horticulture and Soils, Egerton University shares in sights on the disease. Additional reports by Maurice Koome and Simon Kihungu