Source: University of California, Credits David Rosen

Source: Samuel Khabi, Credits: National Museum of Kenya

Kenya’s avocado industry is under mounting pressure from a new and destructive pest: the persea mite (Oligonychus perseae). This invasive spider mite, native to Mexico and first reported in Kenya in Nakuru County in November 2023, has since spread to multiple avocado-growing regions. Though small in size, its impact is proving immense, threatening the productivity, quality, and profitability of a sector that earned Kenya KSh 19.1 billion in export value in 2023.

The seriousness of the threat was underscored in a recent virtual webinar organized by the Fresh Produce Exporters Association of Kenya (FPEAK), where Samuel Khabi detailed the pest’s spread and the urgent need for coordinated management.

How the Mite Spreads, Biology and Life Cycle

Although the mite can disperse naturally through spinning silk threads carried by the wind to neighboring trees, human activity has proven to be its fastest vehicle. Harvesting baskets, dustcoats, pruning tools, and even transport crates have become unsuspecting carriers, moving mites from farm to farm. Infested planting material from uncertified nurseries represents another silent pathway, enabling the pest to establish in new regions unnoticed until damage is visible.

Source: University of California

Once introduced, the mite thrives, particularly under warm and humid conditions, which accelerate its reproduction and establishment.

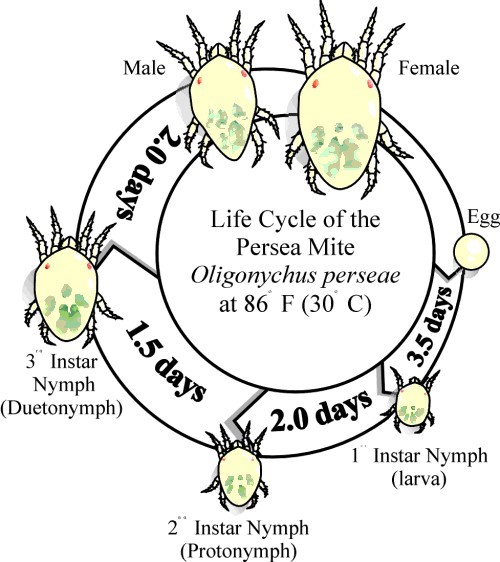

Biologically, the persea mite undergoes five developmental stages, that is, egg, larva, protonymph, deutonymph, and adult.

The adult, a yellowish-green, oval-shaped mite with dark spots, is the most destructive stage. Under favorable temperatures, the full cycle from egg to adult can take just 15 days, allowing populations to build up rapidly

Symptoms and Field Diagnosis

Colonies typically form on the underside of young avocado leaves, where mites puncture cells and suck out chlorophyll, leaving behind distinctive circular necrotic spots. These spots, aligned along the veins and midrib, are a key diagnostic feature. In heavy infestations, mites weave dense silvery webs around feeding sites, protecting themselves and their eggs from predators, rainfall, and even pesticide sprays.

The consequences for trees and farmers are profound. Heavy infestations lead to defoliation, stripping trees of their leaves and exposing fruits and bark to direct sun. This results in sunburn, premature ripening, fruit drop, and lower yields. High mite densities, often exceeding 500 per leaf, can cause near-total defoliation, leaving trees severely weakened and susceptible to other pests and diseases. Farmers in Baringo, Nakuru, and Kisii have already reported yield losses of 30–50 percent in heavily infested orchards.

Photo Credit: KALRO 2025, Credits – Samuel Khabi and AFA -HCD 2025, Credits – Antoninah Lutta

Varietal Susceptibility and Host Range

Varietal susceptibility compounds the challenge. Kenya’s leading export variety, Hass, is among the most affected, along with Gwen and Pinkerton, which suffer high levels of feeding damage. Fuerte shows moderate tolerance, while some traditional local varieties appear resistant even when surrounded by infested trees. Beyond avocado, the mite’s host range includes roses, peaches, grapes, eucalyptus, castor bean, and weeds such as black jack and sow thistle, giving it reservoirs to persist outside avocado orchards

National Implications for Kenya

Kenya is Africa’s leading avocado producer and ranks sixth globally. In 2023, production rose to 632,953 metric tons, with 114,033 tons (21%) exported. Murang’a County alone contributed nearly a quarter of this output, followed by Kisii, Nakuru, Nyeri and Kiambu with nearly a million farmers growing avocados, 70% of them smallholders, any pest that undermines production or export quality threatens not just foreign exchange earnings but also rural livelihoods.

Source: Anita Nduku -Makueni County

Challenges in Managing the Pest

Managing persea mite, however, is no simple task. The pest’s protective webs shield it from sprays, while its rapid reproduction makes it difficult to keep populations below damaging levels. Currently, no pesticide is officially registered for its control in Kenya.

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Options

Instead, experts recommend an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) approach that blends cultural, biological, and when necessary, chemical tools.

Cultural practices include regular scouting every 7–10 days, pruning to open dense canopies, and ensuring good orchard sanitation to prevent mites from hitchhiking on farm equipment. Farmers are advised to source only clean, certified seedlings to avoid spreading the pest into new zones. Alternate host plants, such as weeds and ornamentals that harbor mites, should be removed from around orchards.

Biological, Mechanical, and Chemical Control

Biological control shows promise through predatory mites, which can be released into orchards to suppress persea mite populations. Trials suggest that introducing about 2,000 predators per tree can help restore balance

For small orchards, high-pressure water sprays can physically dislodge mite colonies from leaves. Chemical control, where absolutely necessary, should be based on monitoring thresholds, typically when 70–100 mites per leaf are observed. Low-risk pesticides should be prioritized, and spot treatments are advised to preserve beneficial insects.

Export Market Considerations

For now, persea mite is not listed as a quarantine pest in Kenya’s key export markets, including the EU and Middle East. This gives the industry breathing space. But experts warn that without swift and coordinated management, the pest could damage fruit quality, erode farmer confidence, and weaken Kenya’s competitive edge against global giants like Mexico, Peru, and Colombia.

Collective Action

Beyond the farm level, the manual highlights the need for coordinated stakeholder action. Regulatory agencies such as PCPB, KEPHIS, and the Horticultural Crops Directorate are tasked with developing monitoring protocols, facilitating biopesticide registration, and enforcing compliance. Research institutions like KALRO are expected to investigate resistant varieties and local biocontrol options. County governments are urged to provide farmer training and extension services, while industry associations such as FPEAK are central to building farmer awareness and safeguarding market access

As Khabi emphasized in the FPEAK webinar, the pest may be tiny, but its economic threat is outsized. If unchecked, it could undo much of the progress made in positioning Kenya as a global avocado powerhouse. Protecting the industry will therefore require not only vigilance at farm level but also collective action across research, regulation, and trade.