November 13, 2025

You walk into the bay and notice some plants looking wilted. The irrigation system is working, so what’s going on? Is it drought stress, or is a disease problem starting to develop?

Unfortunately, it’s not always easy to tell. I spoke with several experts to better understand the overlapping symptoms and how to distinguish between the two.

“Drought stress can go hand in hand with disease,” says Carrie Lapaire Harmon, PhD, Extension Plant Pathologist and Director of the Plant Diagnostic Center at the University of Florida. “It doesn’t have to be a standalone, but it can be. That’s why it can be confusing and difficult to know it’s only drought stress.”

Visual Patterns and Symptoms

Wilting plants often point to watering issues, but not always. Other problems can cause similar symptoms, and the visual cues aren’t always obvious. Drought stress typically shows up in a uniform or consistent pattern. For example, all the plants in a particular bay may be uniform to the same degree. “Anytime you see an obvious pattern, you’re going to want to look at what the irrigation is for those areas,” says Harmon.

Talk with the person responsible for that bench or bay to understand recent watering patterns or issues. “The watering person is one of the most valuable employees in the greenhouse,” says James Klett, Professor Emeritus of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture at Colorado State University. “Finding someone who truly understands proper watering is crucial.”

But wilting can also be an early warning sign of disease. “Anything that restricts water movement to the leaves is going to show up as wilt and edge burn – that’s the symptom,” says Harmon. “It’s like a cough in humans, indicating something might be amiss and alerting you to take a closer look.”

Brian Hudelson, Director of the Plant Disease Diagnostics Clinic at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, says root rot is often to blame. “Unfortunately, certain diseases cause similar symptoms to drought stress,” he explains. “In greenhouse settings, I’m especially concerned about root rot pathogens that infect and destroy root tissue, limiting the plant’s ability to take up water. That leads to water stress and symptoms that look just like drought.”

But drought stress isn’t always uniform or easy to spot. Harmon explains that it can sometimes appear in a random pattern, much like disease symptoms. “When canopy closure occurs and you’re using overhead irrigation, some foliage can block water from reaching certain areas,” she says. “This can lead to scattered pockets of drought stress that resemble disease.” Hanging baskets are especially prone to this kind of irregular pattern, she adds.

“I recommend keeping a few ’test plants’ that are more water sensitive,” says Klett. “If they start to wilt, it’s a good sign that other plants might be running low, too. Dahlias, for instance, tend to dry out quickly. In vegetable crops, tomatoes can serve the same purpose. They’re like the canaries in the coal mine when it comes to water needs,” he adds.

Root Inspection Is Essential for Diagnosis

Every expert agreed – when diagnosing drought stress versus root disease, inspecting the roots is essential.

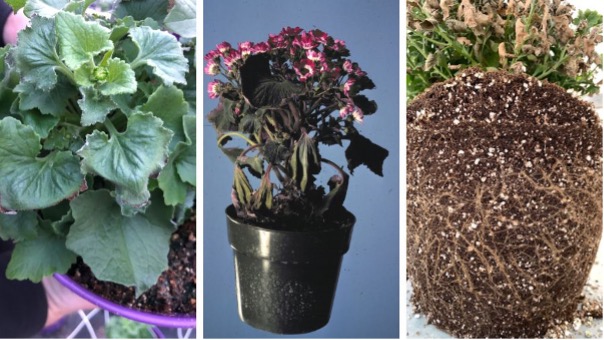

“I pop the plant out of the pot and check the root system,” says Hudelson. “Browning or discoloration in the roots is a sign that there could be disease at play.”

Klett adds, “Look for healthy white fibrous roots wrapping around the container. If you don’t see many, it often points to poor drainage or early root rot caused by overwatering or insufficient dry-down between waterings.”

Nick Flax, Technical Services Specialist at Ball Seed, recommends digging deeper. “If the outer roots look fine but symptoms persist, break open the root mass and check further down. A quick glance at the exterior doesn’t always tell the full story.”

What to Look for in the Root Ball:

- Root zone discoloration

- Blackened or darkened root tips

- Slippage of the root cortex, where the outer layer of the root sloughs off, common in Pythium and Phytophthora infections

- Soft, mushy lesions at the crown

Recovery After Watering: A Key Differentiator

One of the most useful ways to differentiate drought stress from disease is to observe how plants respond after watering. Herbaceous plants stressed by dryness usually perk back up quickly, if no other issues are present.

“With drought stress, they’ll probably come back once watered,” says Klett. “But if it’s a disease setting in, they’re likely to stay wilted and just won’t rebound like a healthy plant.”

Harmon agrees but cautions that early-stage disease can sometimes be deceiving. “A plant might recover overnight, but if it’s diseased, it will gradually get worse and stop bouncing back,” she says. “If it’s truly drought stress, it will typically recover as temperatures cool and the plant catches up.” A good practice is to check for symptoms in the afternoon when stress is most visible, then reassess the next morning to see if recovery has occurred.

Send it to the Lab

If plants don’t bounce back after watering and you’re unsure of the cause, it’s time to get a professional diagnosis. Most plant diagnostic labs offer quick turnaround, and getting an accurate ID will help you treat effectively and avoid unnecessary losses.

“If you hit it with a product without proper identification, the disease can continue to spread,” says Harmon. “You’ve wasted time and money, and the treatment might not even work. It’s especially important to know whether you’re dealing with a true fungus or a water mold, because the control products are very different.”

While waiting for results, Hudelson recommends isolating any suspicious plants. “If you suspect a viral issue – especially one spread by insects – quarantine those plants to prevent it from moving through the greenhouse,” he says. “Even if it’s not a virus, it never hurts to play it safe.”

Courtesy: Greenhouse Grower.