Bʏ Mᴀʀʏ Mᴡᴇɴᴅᴇ,

Kenya’s cut flower industry is steadily increasing its reliance on sea freight as an alternative to air transport, responding to rising logistics costs, global supply chain disruptions, and growing environmental demands from key European markets.

Isaya Muiru of FlowerWatch presented a detailed overview of this trend during a recent industry forum, highlighting the operational realities, emerging opportunities, and persistent challenges facing exporters as they navigate the complexities of long-distance sea freight for perishables.

From Early Trials to a Practical Alternative

While Kenya’s fresh produce industry, especially avocados and mangoes, has long utilized sea freight because of the high cost of air transport for heavy commodities, the flower industry has been slower to adopt it. Muiru explained that sea freight trials for flowers began in 2006 with encouraging results. “The trials of sea flowers by sea was successful,” he recalled. “But then it didn’t pick up because by then the air freight was affordable, space was available, and the difference in cost per kilo was very small.”

He noted that flower exporters at the time were reluctant to risk 30-day transit times, opting instead for the faster, more forgiving nature of air freight.

COVID-19 Crisis: Turning Point for Sea Freight

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic forced a rethink within the floriculture sector. Global flight restrictions and the suspension of passenger flights which traditionally carried significant amounts of flower cargo left exporters without adequate shipping options. “During COVID, the airports closed down. There were no flights, no space. That’s when people started thinking of shipping by sea,” Muiru explained.

With financial support from UK Aid, the industry rapidly organized trial sea shipments, moving at least 20 containers of flowers in a short period. These early trials set the stage for a broader industry shift once the market reopened.

Rising Volumes Amid Red Sea Disruptions

By 2023, conditions had evolved further. Air freight remained expensive and limited, while more shipping lines began offering consistent sea freight services. Additionally, European markets increased pressure on suppliers to reduce their carbon footprint by shifting to sea transport. “The customers in Europe, they are demanding people to ship by sea because of the carbon grid,” Muiru noted.

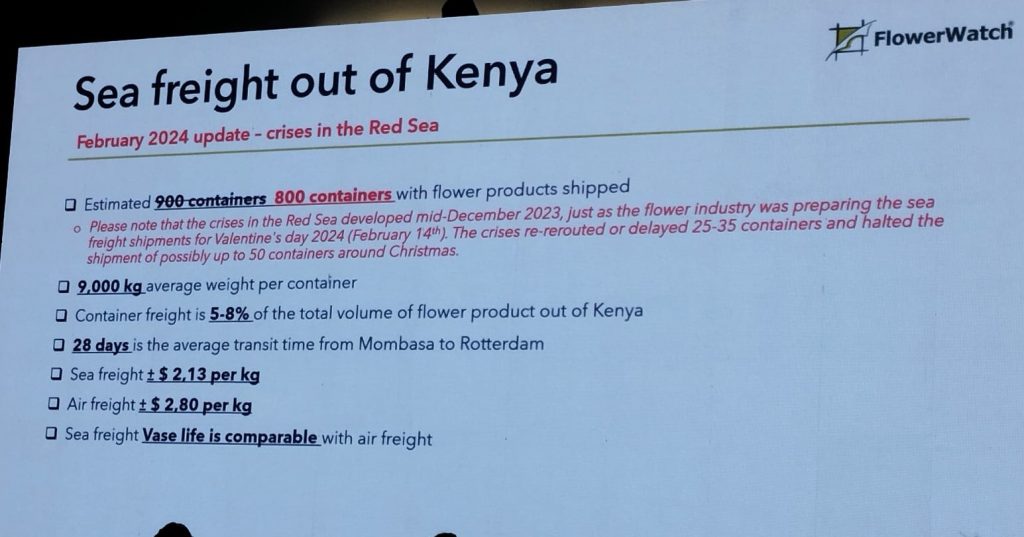

He reported that approximately 9,000 containers of flowers were exported from Kenya by sea in 2023. Transit times averaged between 28 and 35 days, extending to as much as 47 days in isolated cases. The average cost per kilo by sea was $2.13, compared to $2.80 by air. Although the difference in price per kilo appeared marginal, it translated into substantial savings at scale.

Even so, Kenya’s sea freight volumes remain modest compared to competitors like South Africa and Colombia. “9,000 sounds like a lot, but when I share the data for our competitors, it’s quite high,” Muiru acknowledged.

Quality Control and Shelf Life Performance

Concerns around product quality during the extended sea journey have been a longstanding barrier. To address this, Muiru noted that FlowerWatch conducts comparative quality trials in a laboratory in the Netherlands. Identical flower samples from the same farm, same harvest, and same variety are sent by both air and sea for shelf life and vase performance tests.

The results have been consistently promising. “The difference in quality is very small. Actually, the species of flowers you can’t tell whether it was shipped by air or sea when you see it in the vase,” he observed.

Persistent Logistical and Operational Obstacles

Despite the progress, the transition to sea freight has exposed several operational and logistical challenges. Muiru cited instances where cyberattacks on shipping lines, such as the one that hit CMA CGM, resulted in containers being delayed for up to 47 days instead of the expected 35.

Even in such cases, exporters who adhered to strict postharvest and cold chain standards managed to protect product quality. “Even after 47 days, the product was still good. But with 15 different exporters in the same container, three farms lost 30% of their product, while the rest lost between 2 and 15%,” he reported.

Other difficulties highlighted included:

- Inadequate packaging: Some exporters compromised on packaging quality, opting for cheap cartons that weakened under high humidity during the long voyage, causing flower collapse and damage.

- Port delays during peak holiday seasons: In one instance, Mombasa port operations slowed during the December 2022 Christmas break, resulting in delayed container treatment.

- Geopolitical disruptions: Muiru cited the 2021 Suez Canal blockage by the Evergreen vessel and the ongoing Red Sea crisis as significant obstacles. Rerouting vessels around the Cape of Good Hope has increased transit times to between 36 and 45 days.

- Delays during peak market periods: The recent Red Sea conflict coincided with the Valentine’s Day shipping period, causing heavy backlogs.

- Inadequate cold chain facilities at exit points like Mombasa

Rising Costs and the Need for Exporter Readiness

The cost implications of these disruptions have been substantial. Muiru disclosed that the current freight charge stands at about $16,000 per container. “If you calculate the number of stems per container, then it ends up at $1.70 per kilo. If a container has little losses, you get like $2.05 per kilo,” he explained.

He stressed that while sea freight offers significant cost and environmental benefits, it demands much higher discipline and investment in handling, cooling, and packaging than air transport. “Air freight is more forgiving because it’s only maybe three to five days. But for sea freight, which takes 28 to 35, sometimes 47 days, preparation is everything,” Muiru advised.

Recognizing these challenges, FlowerWatch has increased its training programs to help growers and exporters meet the stringent demands of sea freight logistics. “There’s a lot of innovation which can be done, and that’s what we do on the ground training people, preparing them to become sea freight exporters,” Muiru said.

As more exporters adjust their postharvest practices and logistics systems, Kenya’s flower industry is positioning itself to expand its share of sea freighted flowers, ensuring competitiveness in increasingly carbon-conscious global markets.