Soils are the essence of life, sustaining humans, plants, and animals as the source of the food we eat and home for much of the planet’s flora and fauna. Soil health, therefore, is the foundation of health for all plants, animals, and people writes John Ogechah.

Undervalued, neglected resource Undervalued, the soil has become politically and physically neglected, triggering its degradation due to erosion, compaction, salinization, soil organic matter and nutrient depletion, acidification, pollution and other processes caused by unsustainable land management practices. The irony is that the main culprit of soil degradation is the very thing that most rely on healthy soils: agriculture. Industrial agriculture’s intensive production systems, which rely on the heavy application of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, have depleted soil to the point that we are in danger of losing significant portions of arable land.

It is estimated that on nearly one-third of the earth’s land area, land degradation reduces the productive capacity of agricultural land by eroding topsoil and depleting nutrients, resulting in enormous environmental, social and economic costs. Most critically, land degradation reduces soil fertility,, leading to lower yields.

In Africa, the United Nations paints a graver picture: 65 % of arable land, 30 % of grazing land and 20% of forests are already degraded. Locally, there has been concern in recent years about the state of Kenyan soils and the decline in yields in some parts of the country attributed to soil health. The first national soil test carried out across the country revealed a lot of issues ranging from soil pH, limited nutrients and organic matter content in the soil initiative in light of a series of serious challenges impacting our future and perhaps our very existence that we should all surely embrace with open hearts and willing hands!

What is a healthy soil?

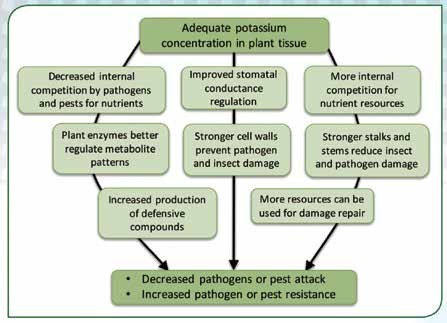

FAO defines soil health as the capacity of soil to function as a living system, with ecosystem and land use boundaries, to sustain plant and animal productivity, maintain or enhance water and air quality, and promote plant and animal health. Healthy soils maintain a diverse community of soil organisms that help to control plant disease, insect and weed pests, form beneficial symbiotic associations with plant roots; recycle essential plant nutrients, improve soil structure with positive repercussions for soil water and nutrient holding capacity, and ultimately improve crop production.

The concept of soil health captures the ecological attributes that are chiefly those associated with the soil biota: its biodiversity, its food web structure, its activity, and the range of functions it performs. At least a quarter of the world’s biodiversity lives underground.

Such organisms, including plant roots, act as the primary agents driving nutrient cycling and help plants by improving nutrient intake, in turn supporting above-ground biodiversity as well. This biological component of the soil system highly depends on the chemical and physical soil components.

There is a price to pay

The green revolution of the past century has seen the constant removal of soil minerals and a loss of two-thirds of the humus that helps to store and deliver those minerals and on which the organisms depend. It is a no-brainer to recognize that every time we harvest a crop from a field, we are removing a little of the minerals that were originally present in those soils. We replace a handful of them, often in an unbalanced fashion, and we decimate our soil life with farm chemicals, many of which are proven biocides. And when We decimate this microbial bridge between soil and plant there is a price to pay. The plant suffers, in that it has less access to the trace minerals that fuel immunity, and the animals and humans eating those plants are also compromised. Restoration of this microbe

bridge between soil and plant through sustainable soil management is key to the achievement of food security and nutrition, climate change adaptation and mitigation and overall sustainable

development. How do we do this?

Composting

Composting, the accelerated conversion of organic matter into stable humus, is much more than just that. When compost is added to the soil, it stimulates and regenerates the soil life responsible for building humus. Compost serves as a microbial inoculum to restore your workforce. A teaspoon of good compost can contain as many as 5 billion organisms and thousands of different species.

These beneficial microbes increase biodiversity and the balance of nature that comes with it. This balance can create a disease-suppressive soil where beneficial organisms neutralize pathogens through competition for nutrients and space, the consumption of plant pathogens, the production of inhibitory compounds, and induced disease resistance through a plant immune-boosting phenomenon called systemic acquired resistance.

Vermicompost (compost produced from worms) is a superior type of compost containing worm castings (worm poop). Castings are loaded with beneficial microorganisms that continuously build fertility in the soil. They are very high in organic matter and humates, which are both extremely important to plant and soil health.

Mycorhiza

Mycorrhizae is a general term describing a symbiotic relationship between a soil fungus and plant root. Mycorrhizal fungi have been lauded as the most important creatures on the planet at this point in time. Apart from enhancing plant growth and vigour by increasing the effective surface area for efficient absorption of essential plant nutrients, these organisms produce a carbon-based substance (called glomalin) that, in turn, triggers the formation of 30% of the stable carbon in our soils. These fungi are endangered organisms as we have lost 90% in farmed soils. Companies have developed mycorrhizal inoculums, allowing farmers to effectively reintroduce these important creatures into farmlands. Compost also has a remarkable capacity to stimulate mycorrhizal fungi.

Pest antagonists

Soil degradation, as explained earlier above, disturbs the balance of nature that keeps pest organisms in check, leading to an upsurge of pests (including diseases). The reintroduction of antagonistic fungi that attack fungi causing root rots such as Fusarium, Rhizoctonia, Pythium, etc., and nematode-attacking fungi that attack plant parasitic nematodes such as root-knot nematodes is another sustainable way of restoring this balance.

Protect soil life

Strategies that promote the survival of soil life and their humus home base must be promoted. There is no point in reintroducing beneficial microbes with one hand and then promptly destroying the new population with the other. The use of unbuffered salt fertilizers kills many beneficial, and over-tillage destroys mycorrhiza. However, the single most destructive component of modern agriculture, in terms of soil life, has been pesticides. Even some ‘safe’ herbicides are more destructive than fungicides in destroying beneficial fungi.

Manage nitrogen

Mismanagement of nitrogen is a major player in the loss of humus. Excess nitrogen stimulates bacteria, and in the absence of applied carbon, they have no choice but to feed on humus. A carbon source should, therefore, be included in all nitrogen applications. We need to regulate N applications (e.g., by adopting foliar application of N) and include a carbon source such as molasses, manure, or compost with every nitrogen application. The carbon source offers an alternative to eating humus.

Turning point

It is not too late to recognize past mistakes and move forward to make this critically important time the turning point. The good news is that the Kenyan agricultural sector is well endowed with a broad range of expertise that is well-positioned and ready to assist commercial growers and rural communities in developing production systems that are economically viable and environmentally intelligent.